Part I: El and Baal, the Shepherd and the Hunter

1. From a town existing 6000 B.C.

In

the oldest agricultural society dug out by James Mellaart in Inner Anatolia at

Catal Huyuk[1] (with 5000 inhabitants

C.H. seems to have existed for 1000 years), the wild bull is a symbol of the

high god, the distant nightly starry heaven with the new-moon as his horns.

Also from Asia Minor comes the cultic cry Jacchos/Jacchê calling upon the god’s

epiphany. Jacchos is Bacchos-Dionysos bougenes

(“the cow-begotten”). Jacchos is connected to the jesting outside the holy area

at Eleusis. On painted jars he is pictured with high hunting boots: He is a

variation on the motif: the great hunter, a motif which also has to be

explained on the basis of the tradition reaching back to Catal Hüyük. His name

is a variant of the old Ja-name. In Pisidia and Cilicia we find the name of a

god Ja as the main element in several theophoric names ex: Iambios (Iia-piia =

“gift of Iia”), cf. the Dionysiac cry jambe

& triambe Latin: triumph[2],

a cry of much the same character as the Jacchos-cry. The purpose of such cultic

calling is to call forth the god. Epiphany is the key to this religion. Tri- is

the god Tarku – also known from Inner Anatolia. The Jahveh name is Gen. 4,26

characterized as very old. John Pairmann Brown[3]

has called our attention to the many similarities that exist between Greek,

Latin and Hebrew sacrificial practice. Even the words used as the “technical

terms” of the cult are identical:

sjor – taurus (“bull”)

lebonah –

libanos – libanum (“incense”)

kuttonet –

chiton (“garment”)

keren – cornu (“horn”)

Even the characteristic biblical phrases originally

built on ritual: to lift one's horn, to sink the horn into the dust and Exod

34,39 has its parallels in classical literature.

A wall painting from the king's palace in Mari shows the

high god sitting on a mountain with the moon on his hat and with the bull as

his animal. He is honored by libations. Philo of Byblos tells us that the

“Highest”, Elioun, was honored with libations after his death. He is Adonis,

god of vegetation and the life-fluids that run in the twigs and make vegetation

sprout in spring and show its fermented power in the wine.

A.Parrot, Le Palais,

Peintures murales, t. XVII.

The aurochs, or the stag, is a personification of the

wild forest and vegetation. In one of the temples is shown the headless corpse,

defenseless, given over to gigantic vultures, a frightening picture of death.

The great horned “bull’s heads” (Greek: bucrania)

must in this setting be seen as a power that gives comfort against death: after

each death due to winter (or summer heat), vegetation will be born again, cf.

the many sculptures showing the goddess in the characteristic posture of giving

birth to a calf, the vegetative power reborn. All these sculptures are seen on

west-walls. Like the sun, the life-powers and the warmth have fled to the west,

to the sunset, but here, in the bosom of the deep starry night, they are born

anew. The bull in this early agricultural religion is a symbol of the

life-power in nature – a power that cannot die, but after each death is reborn

in a new shape (like Osiris, Bata and the Nabataean Tammuz, see below). This

notion about victorious life will,

in the fullness of time, become the belief in sol invictus.

Mellaart, fig. 15

It seems as if the old dying life/bull is shown as the

generative power and direct cause of the goddess giving birth. The old bull is sometimes

placed in a 3-double epiphany under the goddess bringing forth the young calf.

The exact meaning of this bull-trinity is not clear. In his book on the archaic

cult of the bull Ch. Autran[4]

mentions the Lycian god Zeus~Triopas (“with triple Face”). That the highest

reality can show itself to man as a trinity can also be seen in the 3 Gorgos

Perseus confronts in the west, and Geryon in the far west confronted by

Heracles has 3 heads, as Odin in Germanic religion is seen as a trinity (Wotan,

Vile, Ve & Odin, Høder, Lodr giving life to the first humans, Ask and

Embla). A 3-fold epiphany also promises the birth of a child in Gen 18 (see

below).

Western walls. Mellaart. 40 & 37

The last west

wall (Mellaart, fig.20) shows heads of bulls forming the triple bull-symbol in

a sophisticated triple composition (The numbers are added by the present

author):

Where the old highgod, the bull, is

linked to the moon (in Ur and Harran the main god Sin, = the moon, is called

“bull” & “Father of the gods”[5]),

his son is obviously closely linked to the sun and the clear sky of daylight.

He is called Marduc = “calf of the sun”, but he is not directly identified with

the sun, rather seen as the sun hero, the morning star clearing the way for the

sun. Two pictures from Egypt illustrate this: on the first, the calf in the

prow of the sun’s bark penetrating the sea until it reaches the two sycamores

which stand at the gate of paradise, and on the second it goes before the sun

through the gate to paradise[6].

The reverse of two coins from

Palmyra (from Hellenistic period) shows the old god as the “moon-bull”. The

obverse shows the old and the young god face to face, but on the last coin

pictured on each side of the coin[7].

Most important for understanding the religion in Catal

Hüyuk is the understanding of the purposes of the many temples. A bench is

often seen attached to the most southern of the two pillars put into the

eastern wall, and to the same pillar is often attached the united symbol of

male and female god: bull’s horn and breasts with the characteristic open

nipple (and a niche painted red). A restoration of the temple VII layer, no. 35

(Mellaart, fig. 21) shows, over a horned goat’s head, two breasts. Out of the nipples

come the teeth of a fox-cranium and a weasel-cranium. We may presume that the

bench is the place, where a holy drink hidden in the red niche is enjoyed. The

effect of this drink is an ecstatic-mystical experience seen in an archaic

symbolism as the melting together of duality, male and female, into one: On the left side some of the pillars have

one or two breasts, on the right a protruding horn, fig. 24, cf. fig. 39: on

one side two breasts with the beak of the vulture of death as nipples. On the

other side the horn. As the bull is connected to the male god and the right, so

death and the animals that kill and prey on the other animals, and the left,

are closely connected to the female god. The column is a world column and a

symbol of the ladder = the road taken to heaven in ecstasy.

The bench united to the column is the place for the

experience of the ecstatic journey to heaven.

Mellaart, fig.21

Note the many quadrangles coming out from a center

Mellaart, fig. 24

Mellaart, fig.39

C.Colpe has stressed androgynity as the ideal state in

the cult of Attis: Attis living in ecstatic androgynity is tempted by a woman

to realize his manhood, but tries by the drastic act of self castration to

return to androgynity. Androgynity is also expressed in the name Adamna for

Attis (from Ada = “father” and Amma = “mother”, cf. the syrian Atargatis – from ‘Attar + ‘Ate)[8].

There

are a very great number of temples in the oldest layers of the mound: 2 houses

for each temple[9]. Many of

them have two pillars in the eastern

wall: this design is so constant that it must have some specific meaning. It is

the world pillars = the cloven world mountain over which the sun rises in the

east.

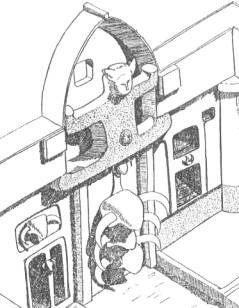

We come across this

design later in Beycesultan in a shrine from a city dug out by S.Lloyd &

J.Mellaart[10]

(reconstruction of altar in shrine below). It must be considered an early

centre for the Luwian culture.

The design can be compared with Mesopotamian

pictures of an eastern gate of the sun.

In a similar shrine were

found flat marble figurines. The long neck is a symbol of ecstasy created by

the unity of left and right:

There

is a high column at one end of the double circle representing the center of the

universe (the world axis) and at the other end two stelae covering the entrance

to the holiest area. They represent the twin-mountains over which the sun rises

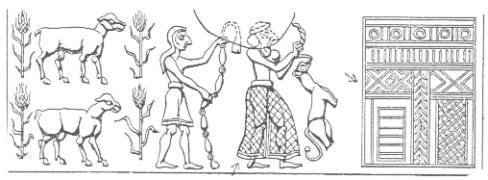

and behind which paradise is found. The Mesopotamian seal shows Shamash

standing over the cloven mountain in the east receiving an offering. Behind him

is the tree of life.

In

Egypt the entrance to the temple was often compared to the hieroglyph “horizon”

showing the twin peaks over which the sun rises. The temple itself is a picture

of the world in the process of creation. The visitor is going from light to

darkness in the Holy of Holies, seen as a symbol of the primeval mount[11].

Mellaart brings a diagram with a review of some of the

walls in the temples. It looks as if all the eastern walls are adorned with two

pillars. This is a small overstatement. But a very large number of east

walls have the pillars and a bench attached to the one closest to the south

wall and in six cases the horn and the breast attached to it.

That

the two pillars of the eastern walls should be interpreted as the world

mountain split into two is confirmed by a painting, which fills out the area

between the two pillars[12]:

www.smm.org/catal/findings/murals.htm

To the

left and right 2 pillars with designs on the side uniting female breasts with

the horn of the bull. In the middle the united “axis mundi”. The two pillars

are the gate of the sun, the world axis or world mountain and primordial

massive split into two, giving room for the rising of the sun. In the center

the united pillar painted with colors (red for man, white for woman) that unite

the duality of the daily world into one. Please note the crosses coming out of

the central pillar. The holy cross unites all 4 cardinal points in a center,

cf. the seals shown underneath. The round stamp has roads coming from left and

right, up and down, all meeting around a center.

![]()

An. St., fig. 4c.

In

Egypt the number “one” was a symbol of the beginning, of primeval time before

“two things came to the world”. Two was the symbol of duality and creation of

up & down, day & night, man &

woman. 4 is the symbol of space and the 4 corners of the world[13].

An. St. 12, pl. Xa

An.

St. 14, fig. 40, 41

White-red “stairs" coming from the right, black

from the left, and, at the top of the mountain, the 4-fold figure as a symbol

of unity and center. We will continually find this movement from duality to

unity from four to one in the symbolism of Catal Hüyük. Mystical experiences of

the unity of all things, coincidentia

oppositorum with male and female as the most important pair of opposites

seems very important for this religious art, more important than the chaos -

cosmos symbolism. In historical time we will meet these speculations about the monade, the single point and the duade as its negative counterpart in

Pythagoraean philosophy.

The stamps mentioned above are the closest we come to

the later so well known yin-yang symbol. The bands of decoration on the next

picture show two opposites melting together in the wholeness of the fourfold

design. This design is a forerunner of the yin-yang-symbol. To the left:

light-colored triangles put together with their reflected images in dark color

to a running band.

Mellaart, fig. 14.

We have chosen to show some examples of the symbol of the cross as the 4 cardinal points coming out of the mystical center or being united into the mystical omphalos. They are all found at Catal Hüyük.

http://catal.arch.cam.ac.uk/catal/archive%5Frep97/turkan97.html

Mellaart, fig. 32

An.

St. 14, pl. XIII

The double-gate is, acc to Mellaart, a stylized relief of the goddess and

her daughter[14]. But there

is no passage through this "gate". It is certainly a symbol of the

goddess, for the gate-design is very similar to the many sculptures of the

leopard-goddess spreading her legs widely obviously in a posture of giving

birth. But the square “gate” is a symbol of the double goddess as the primeval

massive block of unformed matter, the world mountain as central pillar

surrounded by the two pillars of the gate of the sunrise. The oldest name of

Cybele: Cubaba has obviously something to do with Latin cubus, Greek kabos,

Hebrew qab, a cubic unit, Arab Ka´aba. In Petra the symbol of al Uzza, the

goddess, was a square block.

In classical Greek literature we find the mentioning of Xthonie’s and

Harmonia’s wedding dress. Xth.’s dress is given her by Zas acc. to Pherecydes.

Cosmos and the patterns creating cosmos out of materiam primam is a dress covering the goddess of the earth. In

C.H. we find the goddess in the posture of giving birth covered by a full

pattern and all the patterns centered round the fruitful navel as the basis of

a column of 5 omphalos-symbols.

It is told by Pherecydes: “Zas made an overcoat (Greek: faros), big and beautiful and

embroidered with colors. On it were Earth and Ogenos (Oceanos) and the house of

Ogenos.” This coat is given to the first female principle, Xthonie, who then

takes the name Ge (earth).

“So is also by Orpheus Kore as supervisor of all the sown land spoken of

as a weaver”(Abel, Orphica frgm.211).

Penelope is weaving a dress that dissolves by night and is remade every

morning. (With the coming of darkness, the contours of cosmos are wiped out.)

Acc. to Proclus Plat.Crat.p.24 Kore

and her girls, while still on the earth, are weaving “the whole order of life”.

Claudian depicts how Kore is sitting weaving a dress for Demeter with the 5

zones and their vegetation and surrounded by Oceanos, Raptus Pros.I 237ff. Eph 3,10 speaks of God’s many-colored Sophia

made known to the chaos-powers of the universe. The same Greek word is used to

characterize Xthonie's dress: ”worked with many colors” (polypoikilos).

It is our strong conviction that early tantric thinking about the male

and female forces of the universe is a key to the religion in Catal Hüyük: the

naked goddess radiating massive female sexuality is pure and untamed shakti.

(See below the chapter on the coiled snake.) Creation is the female power

tamed, covered and made into fruitful earth (Pherecydes). In India the

shakti-force is situated at the bottom of the spine, and can be made to ascend

through several centers along the spinal cord. This notion is the key to the

ascending row of 5 omphalos-symbols in the painting on the foregoing page.

The

mystical quadrangle is found everywhere in prehistoric art. It shows the 4

corners of the world surrounding omphalos, cf. in the Bible the 4 rivers with

their common outspring in the Garden of Eden.

The

opposite movement from east, west, north and south towards the world’s omphalos

is seen Ez 38,5f. + 12. The quadrangle is also seen on a temple in Uruk and in Halaf

(together with the snake-coil, see below) and on the leopard-goddess’ cloak and

the kilt of the hunter. In Uruk the kilt consists of quadrangles. In Susa it is

adorned with 2 big quadrangles, each with 8 lines coming out of a center.

Seal from Uruk, Frankfort, p.19

Amulets from Arpachhiyya, Mallowan, Iraq 2, frig 50.

Seal from Susa le Breton, RA L, 1956, p.135.

The mystical quadrangle or cross is – together with the 4-

or 8-petalled rosette the most important symbol of the Halafian culture and its

descendants in the Tepe Gawra, Tell Brak and Arpachhiyya. It is everywhere on

drinking vessels and amulets.We have here the beginning of the tantric mandala, which often unites triangle

and quadrangle with the 8- or 16-petalled lotus.

Many classical authors mention the special importance the Cappadocians

gave to the plant Ruta.

It is a highly aromatic shrub found on rocky hillsides. Its pungent smell

made it an often-used medicine and it was even thought to be an antidote

against deadly drugs.

In German it is called cross-r. “Kreuzraute”,

obviously because of its side-flowers, which have 4 petals (the top-flower has

5). Its flowers look very much like the mystical flower of the Catal Hüyük

temples.

Painted ceramic from Arpahiyah, end of the 5th

mill.B.C. Brit.Mus.

Ur, early 4th mill.B.C.

At the bottom “the mystical flower”, a symbol of the mystical center, where the well of life divides into 4 streams, and where the plant of life is unfolding its beauty. That this is the meaning of the symbol is seen even more clearly on the plate from Ur: from the round navel emerge 4 streams of water going out to the 4 cardinal points. The cross or the cross—flower is a symbol of the mystical center of the world, of all diversity coming into unity, of mystical vision. It can also be shown in the center of a circle made by the great horns of the divine goat.

Tepe Siyalk, South of Teheran 2nd half of the 4th

mill.B.C.

R.Wood, The Ruins of Palmyra,

1753, pl.XIX.

The symbolism of the world mountain split into

two has survived in Inner Anatolia and is still very much alive in the time of

the Roman coinage. A.B.Cook[15]

brings the picture of 3 coins from Caesarea in Cappadocia (The first two are

from his own collection, the last from Brit.

Mus. Cat. Coins Galatia, pl.13, 1, 2). The mountain shown is Mt. Argaios

outside the city (the highest in Anatolia): on the first coin it is

conventionalised to the world mountain flanked by the two pillars. The two

pillars are covered with green foliage. On the mountain a dog is seen hunting a

stag or a similar animal. On the next coin the mountain is conventionalised to

a pyramid. With the giant head of a billy-goat, the mountain is made one with

the high-god and the wild goat as his epiphany. The last coin shows the two

pillars separated from the mountain, building some kind of gate to the

mountain. Strange is the mysterious  rosette placed in the centre of the

mountain massive. Is it witness to the fact that the mountain was seen as the

place where a mystical flower grew, Cook asks; and he brings the following

legend heard by a modern traveller in the area[16]:

a traveler

once came from Frangistan, in search of a rare plant which grew only on the

summit of Argaeus, having ten leaves round its stalk and a flower in the center. Here it was said to be

guarded by a watchful serpent, which only slept one hour out of the

four-and-twenty. The traveler in vain tried to persuade some of the natives to

accompany him, and point out the way; none of them would venture, and at length

he made the ascent alone. Failing, however, in his

attempt to surprise the dragon, he was himself destroyed. The story adds that

he was afterwards discovered, transformed into a book, which was taken to

Caesareia, and thence found its way back into Frangistan. This tale reminds one of the old

Mesopotamian tradition about the herb of life guarded by a snake. His

transformation into a book proves that the flower is the symbol of ultimate

wisdom. A roof at the Southern end of the Bel temple in Palmyra shows the

mystical flower surrounded by the twisted roads of the labyrinth.

rosette placed in the centre of the

mountain massive. Is it witness to the fact that the mountain was seen as the

place where a mystical flower grew, Cook asks; and he brings the following

legend heard by a modern traveller in the area[16]:

a traveler

once came from Frangistan, in search of a rare plant which grew only on the

summit of Argaeus, having ten leaves round its stalk and a flower in the center. Here it was said to be

guarded by a watchful serpent, which only slept one hour out of the

four-and-twenty. The traveler in vain tried to persuade some of the natives to

accompany him, and point out the way; none of them would venture, and at length

he made the ascent alone. Failing, however, in his

attempt to surprise the dragon, he was himself destroyed. The story adds that

he was afterwards discovered, transformed into a book, which was taken to

Caesareia, and thence found its way back into Frangistan. This tale reminds one of the old

Mesopotamian tradition about the herb of life guarded by a snake. His

transformation into a book proves that the flower is the symbol of ultimate

wisdom. A roof at the Southern end of the Bel temple in Palmyra shows the

mystical flower surrounded by the twisted roads of the labyrinth.

The black triangle with the ”staircase”

and at the centre the mystical cross or flower is a symbol of the primeval

hill, the world mountain. The coins are witness to a tradition going back 6000

years.

In the wall-paintings of Catal Hüyük both bull and stag are seen hunted down

by hunters with a leopard’s skin fastened to the belt. The leopard is also

found as the animal on which the goddess

and her boy child ride. As the

bull clearly is a symbol of the highgod, the male god, it is reasonable to

assume, that this god is a suffering and dying god, killed by the younger god

and his followers, perhaps on the instigation of the goddess. Clearly there is

some conflict between the bull/stag and the leopard, see the decoration from

one of the temples showing the bull’s horn broken off by the leopard. Later we

will find the motif, the bull/stag killed by the lion, as one of the most

important motifs in religious art in Asia Minor and Syria and Mesopotamia.

An.St. 12, pl.XI

An.St.

13, p.71

A strong and powerful high god is

killed by a younger god with demonic features being a cruel killer like a beast

of prey. He has drunk the milk of the goddess whose breasts are modelled on the

temple walls, but often with an open hole where the nipple should be, and out

of the hole point the terrible tusks of a wild boar or the red beak of a

vulture, the bird who, acc. to Mellaart, plays the final role in the funeral

ritual cleaning the skeleton of flesh. It seems very logical to interpret this

strange symbol, the open breast, as pointing to some God-given drink of an

euphoric demoniac character, cf. the myth about how Dumuzi, the Sumerian god of

vegetation, the shepherd, is killed by demons from the nether world and Actaeon

torn to pieces by the hunting dogs, both in the physical form of a stag or

gazelle, while Dionysos is torn up by maenads with fox skin fastened to their

belts.

An.

St. 12, pl. 14

The demonic character of this pack

of hunters is stressed by the fact that some of the hunters are without a head

and with a body half white, half red. The next picture is interesting because

it shows the triple symbol of the divine bull set in contrast to two rows of

boar tusks. Acc. to traditions much later, the god of vegetation, Adonis, is

killed by a boar and Attis suffers death acc. to one version (by Herodot) on a

boar hunt. Note how the bull on the north wall is surrounded by (life-)fluids.

In Catal Hüyük there seems to be

traces of a ritual hunt with a very dramatic end: the young god and his

follower murdering the old high god in the physical form of the stag or the

wild aurochs.

The triple bull is shown between the two pillars of the East wall, in

"the Gate of the Sun-rise".

Mellaart,

fig. 41.

In Catal Hüyük the deceased were

buried under the floor obviously because the living wanted to continue a kind

of contact with their spirits. Only one – to judge from his skeleton suffering

from serious illness – was found buried outside. Perhaps some poor outcast. A

typical building recently dug out, has a number of bodies set to rest under the

floor in two groups, one in the North-western corner and the other close to the

Northern wall. The first group (at least 14) were almost all children, the next

(at least 15) a mixture of children and grown ups. A third group was set to

rest between the two sacred benches going out from the Eastern wall, they were

all adults (8). There must be some specific meaning connected to this location

of the bodies of the most important members of the household: they are buried

in the holy direction of the rising sun close to an arrangement similar to the

two pillars forming the gate of the sun in most of the temple rooms[17].

It is very important for the

understanding of the nature of religion and its early beginnings in the oldest

agricultural society, that it seems to rise from the experience of two great

forces permeating the nature giving growth to the crop in spring, and later in

the heat of the high summer giving death to nature. Religion is not a mixture

of human inventions but founded on experience even to the degree that the force

of death is integrated into the killing instincts of man as hunter and warrior.

But the strong creative force is able to conquer even death – so it is felt. As

the sun rises out of darkness, so will a redeemer stand forward on the dust of

death.

A.J.Tobler,

Excavation at Tepe Gawra,II ,1960,

no. 81. .Oppenheim, Tell Halaf I,

t.LX. Wooley IRAQ 1, 1934, pl. XX.

The Halafian culture in Northern

Iraq (named after Tell Halaf dug out by a German team under Max von Oppenheim but

its typical ceramic has been found over a big area 5000 B.C.) and Tepe Gawra,

24 km NE of Mosul represent a culture prior to the arrival of the Sumerians.

Ceramics from Tepe Gawra show a man

with a skin tied to his waist and a curved club in his hand and an extremely

long pigtail

In Halaf a similar skin tied to the

waist could perhaps be seen on a row of dancers. Already in 1913 traces of the

Halaf culture was found by C.Leonard Wooley in Yunus by Karkemish. We see a man

with the skin of an animal with a long tail tied to his waist. Cf. that the

kilts little by little replacing the skin both in Egypt and in Early Susa have

an animal's tail attached to them. The Yunus potsherds also show bull's heads

and bucrania set on a high pole with

raindrops dripping from their horns or even mystical, 8-petal flowers dripping

from their curved horns. From Tepe Gawra there is a very beautiful 16-petal

flower with 4 streams of water falling from its mystical centre, cf. the

mandala-pattern. Very often the bowls are decorated with the mystical flower at

the bottom seen as the centre of many waves of water.

Tepe Gawra no.54

Tepe Gawra no.54 pl. CLIX,

12 & CLVIII, 1

pl. CLIX,

12 & CLVIII, 1 Halaf I, XXIX

Halaf I, XXIX

Mallowan, Iraq II

Mallowan, Iraq II Tepe Gawra, no. 265

Tepe Gawra, no. 265 & no.86

& no.86

Amiet 1582

Amiet 1582  Tepe Gawra, no.91

Tepe Gawra, no.91

The dancers from Halaf are shown

with a very high hairdo. A long waving hairdo is the symbol of ecstasy, of the

head (mind) being dramatically expanded upwards. Another scene from a seal

(this time from Tell Brak, an offshoot of the Halaf culture) shows a man doing

an act of indecency to another man. He has long waving hair and perhaps even a

feather in top of the hairdo and carries a kind of kilt with something hanging

down from the brim perhaps the paws and tail of the skinned animal. A leopard

is seen on a potsherd from Tepe Gawra. Note the way the claws are set off from

the paws. A woman (?) is taken from behind while a donkey watches the scenery

cf. a stamp from Luristan showing a girl with long plated hair doing a sexual

act with a bearded man while a dog watches). Perhaps they have all been warming

up by the enormous ale-jar.